CA Foundation Business Laws Study Material Chapter 10 Formation of Contract of Sale

INTRODUCTION

The Sale of Goods Act, 1930, governs transfer of property in goods. It does not include transfer of immovable property which is governed by the Transfer of Property Act, 1882.

- Contract of Sale of Goods is a special contract. Originally, it was part of Indian Contract Act itself in chapter VII (sections 76 to 123). Later these sections in Contract Act were deleted, and separate Sale of Goods Act was passed in 1930.

- The Sale of Goods Act, 1930, contains 66 sections in VII Chapters. It came into force on the 1st of July 1930 as, ‘The Indian Sale of Goods Act, 1930’. Later in 1963, the word “Indian” was omitted and it became “The Sale of Goods Act, 1930”.

- The Sale of Goods Act, extends to the whole of India except the State of Jammu and Kashmir.

- As per section 3 of the Sale of Goods Act, the principles of the Contract Act relating to formation of contract, performance of contract, law of damages etc. are also applicable to contract of the sale of goods insofar as they are not inconsistent with the express provisions of the Sale of Goods Act.

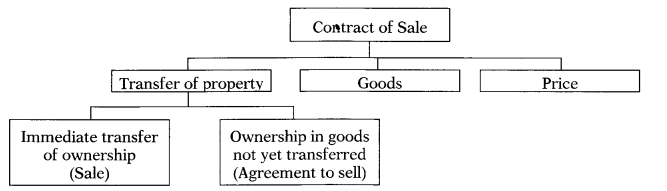

A. WHAT IS A CONTRACT OF SALE?

Sec. 4(1) of the Sale of Goods Act defines a contract of sale of goods as -“a contract whereby the seller transfers or agrees to transfer the property in goods to the buyer for a price”.

contract of sale of goods, like any other contract, results by an offer by one party and its acceptance by the other. The parties are free to decide the terms and conditions of performance of their contract. Wherever the contract is silent, rules provided by the Sale of Goods Act apply to the relevant issue.

Buyer means a person who buys or agrees to buy goods. [Sec. 2(1)]

Seller means a person who sells or agrees to sell goods. [Sec. 2(13)]

Property means the general property in goods, and not merely a special property. Sec. 2(11). Property means ownership. If A who owns goods pledges them for raising money to B, A has the general property in the goods, while B (pledgee, person with whom goods are pledged) has a special property or interest in them, e.g. pledgee has a right to retain the pledged goods until he is paid by A (pledgor) the entire amount of his loan with interest.

Essential characteristics of a contract of sale

- Two parties – there must be two parties a buyer and a seller.

- Transfer of property – a transfer of property i.e. ownership, in goods from the seller to the buyer must take place (in the case of sale) or ownership should be agreed to be transferred (in the case of agreement to sell)

- Goods – the subject matter of sale must be goods.

- Price – transfer of property must take place for some money consideration called price.

- It includes both a ‘sale’and ‘an agreement to sell’.

- A contract of sale may be absolute or conditional [Sec. 4(2)].

- It may be in writing/oral or implied

- Essential elements of a valid contract must be present.

B. SALE & AGREEMENT TO SELL

A contract for the sale of goods may be either a sale or an agreement to sell.

Sale

Where under a contract of sale the property in the goods (Le. the ownership) is transferred from the seller to the buyer the contract is called a sale. Sec. 4(3). The transaction is a sale even though the price is payable at a later date or delivery is to be given in the future, provided the ownership of the goods is transferred from the seller to the buyer.

Example: S makes a contract with P for sale of his Nano Car for Rs. 80,000. P makes the payment and takes the delivery of car. This is the transaction of sale where the ownership has passed from S to P for a price.

Agreement to sell

When the transfer of ownership is to take place at a future time or subject to some condition to be fulfilled later, the contract is called an agreement to sell. [Sec. 4(3)]

Example: S agrees to sell his Car to P for Rs. 2,00,000 after one month. P agrees to buy the car and make payment after one month. This an agreement to sell and it will become a sale after one month when P make the payment and gets the ownership of car.

The conditional contract of sale like goods sent op “sale or return” basis are in the nature of an agreement to sell.

When an agreement to sell becomes a sale?

An agreement to sell becomes a sale when the prescribed time elapses or the conditions, subject to which the property in the goods is to be transferred, are fulfilled. [Sec. 4(4)]

Thus, if goods are delivered to the buyer on approval Le. “on sale or return”, the transaction is an agreement to sell, but it becomes a sale and the property in the goods passes to the buyer where the buyer gives his approval or acceptance to the seller.

| SALE | AGREEMENT TO SELL | |

1. Transfer of property | The title to the goods passes to the buyer immediately. | The title to the goods passes to the buyer on future date or on fulfilment of some condition. |

2. Nature of Contract | It is an executed contract. | It is an executory contract. |

3. Burden of risk | Risk of loss is that of buyer since risk follows ownership. | Risk of loss is that of seller. |

4. Nature of rights | It creates jus in rem that is the buyer as a owner gets the right to enjoy the goods against the whole world. If the seller refuses to deliver the goods the buyer may sue for recovery of goods by specific performance. | It creates jus in personam that is the buyer has only a personal remedy against the seller. He can sue only for damages for breach and not for recovery of goods. |

5. Remedies for breach | If the buyer fails to pay for the goods, the seller may sue for the price (suit for price sec. 55) and also has other remedies available to an unpaid seller. | If the buyer fails to accept and pay for the goods, the seller can only sue for damages and not for price. (Damages for nonacceptance sec. 56) |

6. Insolvency of Buyer | If the buyer becomes insolvent before paying the price, the seller shall have to deliver the goods to the Official Receiver on his demand because the ownership of the goods has passed to the buyer. | Since the seller continues to be the owner, he can refuse to deliver the goods to the Official Receiver unless he is paid the price because the seller continuous to be the owner of the goods. |

7. Insolvency of Seller | If the seller becomes insolvent while the goods are still in his possession, the buyer shall have a right to claim the goods from the Official Receiver because the ownership of goods has passed to the buyer. | If the seller becomes insolvent, the buyer cannot claim the goods. If the buyer has paid the price he can claim ratable dividend from the estate of the insolvent seller. |

Sale & Hire-Purchase

Hire purchase agreement is a contract for the hire of an asset, which contains a provision giving the hirer an option to purchase. A hire purchase agreement has two elements:

- Element of bailment, since the possession of goods is given to the buyer

- Element of sale, since it contemplates an eventual sale.

The hirer is given an option either to become the owner after the payment of the stipulated hire charges/instalments or to return the goods and put an end to the hiring. The agreement must give the hirer an option to terminate the agreement and to refuse payment for further instalments, if he so desires. If the hirer defaults in paying the instalments, the seller can terminate the agreement and resume the possession of the goods.

If there is an immediate transfer of ownership of goods, it is a sale, even though, the price is paid by instalments.

SALE | HIRE-PURCHASE | |

(1) | In a contract of sale, the seller transfers or agrees to transfer the property in goods to the buyer for a price. | In hire purchase there is an agreement for the hire of an asset conferring an option to purchase. |

(2) | The ownership in goods passes on making the contract even if price is paid in instalments. | The ownership passes when the option to purchase is finally exercised by the intending purchaser after complying with the terms of agreement. |

(3) | The purchaser becomes owner of goods | In a hire-purchase the hirer is not the owner but only a bailee of goods. |

(4) | After a sale takes place the buyer cannot terminate the contract and refuse to pay the price of the goods. | In a hire-purchase the hire purchaser can terminate the contract at any time and he is not bound to pay any further instalments. |

(5) | On default by the buyer the seller cannot claim back the goods. | On default of any payment by the hirer, the owner of the article has the right to terminate the agreement and to regain the possession of the article. |

Sale and contract for work and labour

A contract of sale involves transfer of property in goods for a price. A contract for work and labour involves exercise of skill or labour. The main object is providing service by using skills, though goods are also delivered under the contract. For example, where a goldsmith is given gold for making ornaments or an artist is given paint and canvas to paint a picture, These are contracts of work and labour.

- Nagpur Computer Services Ltd. has taken a comprehensive maintenance contract of computers which covers not only the maintenance of computers but also the supply of spares. This is a contract of work and labour.

- A lady gave a plain saree to Jariwala Brothers for embroidering with Jari, to be purchased by Jariwala Brothers. It was held by the court that it was contract for work and labour and not a sale.

Sale and bailment

In case of bailment possession of goods is transferred from the bailor to bailee for some purpose, e.g., safe custody, repair, etc. The goods are to be returned on the fulfilment of purpose. In case of sale there is transfer of ownership, and the question of return of goods does not arise. The following are the points of distinction:

| SALE | BAILMENT | |

(1) | In a contract of sale, the seller transfers or agrees to transfer the property in goods to the buyer for a price. | In case of bailment possession of goods is transferred from the bailor to bailee for some purpose, e.g., safe custody, repair, etc. |

(2) | The buyer can deal with the goods the way he likes. | The bailee can use the goods only for the intended purpose of bailment |

(3) | The buyer gets ownership of the goods. | The bailee only acquires possession. |

(4) | Generally, the goods are not returnable in a contract of sale. | The goods are returnable after a specified period or when the purpose for which they were delivered is achieved. |

(5) | The consideration for a sale is the price in terms of money. | The consideration for bailment may be gratuitous or non-gratuitous. |

C. FORMALITIES OF CONTRACT OF SALE [SEC. 5]

A contract of sale is formed by offer and acceptance. There is an offer to sell or buy goods for a price and the acceptance of such an offer.

– The contract shall provide for delivery of goods. Delivery may be immediate, simultaneous, by instalments or in future.

– The contract shall provide for payment of price. Payment of price may be immediate, simultaneous, by instalments or in future.

Contract of Sale. – How it is Made?

- May be in writing

- May be by word of mouth

- May be partly in writing and partly oral

- May be implied from the conduct of parties or by course of their business.

D. GOODS: SUBJECT MATTER OF CONTRACT OF SALE

Goods means—

every kind of movable property other than actionable claims and money.

and includes – stock and shares, growing crops, grass, and things attached to or forming part of the land which are agreed to be severed before sale or under the contract of sale. Section 2(7).

Actionable claim means a right to a debt or to any beneficial interest in movable property not in the possession of the claimant, which can be recovered by a suit or legal action. Money means the legal tender or currency of the country and It does not include old coins and foreign currency.

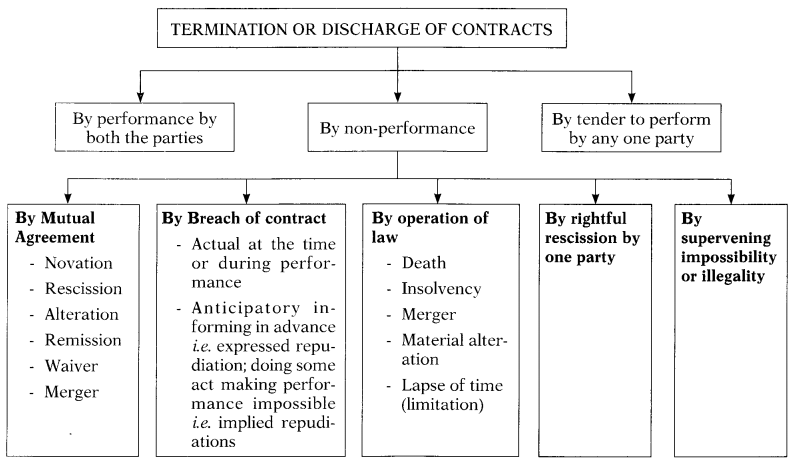

A. Classification of Goods

- Existing Goods

- Specific

- Ascertained

- Unascertained

- Future Goods

- Contingent Goods

1. Existing goods

A. Specific goods

The goods which are identified and agreed upon at the time when the contract of sale is §; made, are called ‘specific goods’ (Section 2(14). For example, a Videocon washing machine, a specified and finally decided car or scooter etc.

B. Ascertained goods

The term ‘ascertained goods’ is not defined in the Sale of Goods Act but has been judicially interpreted. Ascertained goods are those goods which are identified in accordance with the agreement after the contract of sale is made. When out of a large number or large quantity * of unascertained goods, the number or quantity contracted for is identified and set aside for such contract, such number or quantity is said to be ‘ascertained goods’. E.g. A whole seller of wheat has 100 bags in his godown. He agrees to sell 10 bags of wheat and these bags are identified and set aside. On selection the goods become ascertained.

Both, specific or ascertained goods in the ultimate analysis mean identified goods. The dif-ference is in the point of time when identified. In case of specific goods, they are identified at the time of making of the contract, while in case of ascertained goods, they are identified after the making but before the performance of the contract, the process being conducted in conformity with the agreement. ,

C. Unascertained goods

The goods which are not specifically identified and agreed upon at the time when the contract of sale is made, are called ‘un-ascertained goods’. For example, X is a wholesaler dealing in wheat. He agrees to sell 50 bags of wheat to Y. This contract is for the sale of un-ascertained goods because the bags of wheat have not been identified at the time of the contract of sale.

If I have 3 cars of the same kind and I offer to sell one particular car, the goods are un-ascertained till one particular car is appropriated towards the contract. On appropriation the goods become ascertained. If the identity of contract goods is not established by appropriating them towards the contract, the contract remains in respect of un-ascertained goods.

2. Future goods

Those goods which are yet to be manufactured or produced or acquiredby the seller after the making of the contract of sale, are called ‘future goods’. Sec. 2(6). For e.g. A gives an advance of t 2 lakhs for booking a Maruti car which is to be delivered after three months. This is the contract for the sale of future goods. A contract for the sale of future goods is always an agreement to sell It is never actual sale because a man cannot transfer what is not in existence.

3. Contingent goods

As per section 6(2) of the Act, contingent goods are those goods the acquisition of which by the seller depends upon a contingency (uncertain event) which may or may not happen. It may be noted that although the contingent goods are a type of future goods but they are different from future goods in the sense that the procurement of contingent goods is dependent upon an uncertain event or uncertainty of occurrence, whereas the obtaining of future goods does not depend upon any uncertainty of occurrence.

Example: A car dealer agrees to sell a yellow colour car to a customer provided it is available with the manufacturer. This agreement is for a sale of contingent goods and it will become void if the yellow colour car is not available with the manufacturer.

Quality of Goods includes their stai^ or condition. [Sec. 2(12)]

B. Effect of Destruction or Perishing of Goods

The destruction or perishing of goods may take at any of the following stages:

a. Goods perishing before making the contract [Section 7]

- Where specific goods had perished or become damaged

- before the contract was made

- without the knowledge of the seller, the contract is void.

Thus, the contract of sale shall be void on the perishing of goods, if the following conditions are satisfied:

- It must be a contract for sale of specific goods;

- The goods must have perished before making the contract; and

- The seller must not be aware of the perishing or damaging.

Example: A agrees to sell B a certain horse. It turns out, that the horse was dead at the time of agreement, though neither party was aware of the fact. The agreement is void.

b. Goods perishing before sale but after agreement to sell [Section 8]

- Where specific goods had perished or became damaged

- without the fault of seller or buyer

- after the agreement to sell is made and before the risk passes to the buyer

- the contract becomes void.

Thus, the agreement to sell become void in the following circumstances:

- The contract of sale must be an agreement to sale and an actual sale

- The agreement to sale must be for specific goods

- The goods must perish or become damaged after agreement to sale but before sale

- The goods get perished or damaged without any wrongful act or default on the part of the seller or the buyer.

For example, an agreement to sell a car after a certain period becomes void, if the car is de-stroyed or damaged in the intervening period.

Note:

- Perishing of goods means not only physical destruction of the goods but it also covers loss by theft or the loss in the commercial value of the goods (e.g. where cement is spoiled by water and becomes stone)

- It should be noted that both the Sections 7 and 8 as mentioned above, apply only to ‘specific goods’. It is only perishing of specific and ascertained goods that affects a contract of sale. Where, un-ascertained goods are perished the contract will remain valid and the seller is bound to supply the goods. For example if X agrees to sell to Y 10 bags of wheat out of 100 bags lying in his godown and the bags in the godown are totally destroyed by fire, the contract does not become void. X must supply 10 bags of wheat or pay damages for the breach.

E. PRICE

Price is an essential condition of a contract of sale of goods. According to Section 2(10), price is the

money consideration for a sale of goods. Money means legal tender money in circulation. Old and

rare coins are not included in the definition of money.

How is the price of the goods ascertained?

Section 9 provides 4 modes of ascertainment of price. The price in a contract of sale may be—

- fixed by the contract

- may be left to be fixed in an agreed manner (such as market price or fixation of price by a third party).

- may be determined by the course of dealings between parties, (such as manufacturing cost, market price).

- a reasonable price (if price cannot be fixed in accordance with the above provisions).

What is a reasonable price is a question of fact dependent on the circumstances of each particular case. [Sec. 9(2)]

Consequence of Non-Fixation of Price by Third Party [Section 10]

- The parties may agree to sell and buy goods on the terms that the price is to be fixed by the valuation of a third party. If such third party fails to make the valuation the contract becomes void.

- However, if the buyer has received and appropriated the goods or any part thereof, he becomes bound to pay reasonable price.

- If the third party is prevented from making the valuation by the fault of the seller or the buyer, the innocent party may maintain suit for damages against the party in fault.

Stipulations regarding payment of price [Sec. 11]

In a contract of sale, stipulations as to time may be of two kinds:

– Stipulations relating to time of payment, and

– Stipulations not relating to time of payment, for e.g. relating to time of delivery of goods

- Stipulations as to time for payment of price are not regarded as essence of contract, unless a different intention appears from the terms of the contract. Thus if the payment is not made in time, the seller cannot avoid the contract but can claim damages. For example A sells a laptop computer to B with a stipulation that payment should be made within 3 days. B makes the payment after 7 days of the contract. Here A cannot avoid the contract on the ground of breach of stipulation as to time of payment.

However, time of payment can be made essence of the contract, if there is an express provision in the contract of sale. If there is no express provision in the contract of sale, with regard to time of payment, then time of payment is not deemed to be the essence of contract. - Whether any other stipulation as to time (c.g. of delivery of goods) is of the essence of contract, will depend upon the terms agreed upon. It means that time of delivery of goods etc., can also be made essence of the contract of sale if an express provision to this effect is made in it. If no such provision is made, then time of delivery of goods will not be the essence of contract. (Sec. 11) Suppose if time of delivery of goods is made the essence of the contract of sale by providing express terms in this regard – what will be the remedy for the buyer, if the seller does not make the delivery within the stipulated time? (The buyer can avoid the contract)

- It may be noted that in ordinary commercial contracts for sale of goods, time is prima facie of the essence with respect to delivery.

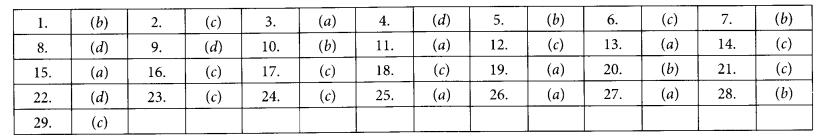

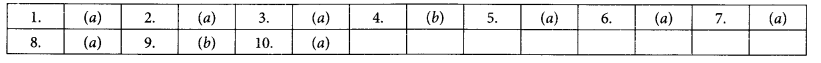

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS:

1. The code governing sale of goods was earlier contained in

(a) the Indian Contract Act

(b) the Transfer of Property Act

(c) the Hire Purchase Act

(d) None of the above

2. The Sale of Goods Act, 1930 governs the transfer of property in

(a) movable property

(b) immovable property

(c) both movable and immovable property

(d) all type of properties

3. “Goods” means

(a) every kind of movable property other than actionable claims and money

(b) some kinds of immovable property only

(c) every kind of movable property including actionable claims and money

(d) Both ‘a’ and ‘b’

4. Where under a contract of sale the property in goods is transferred from the seller to the buyer, the contract is called.

(a) an agreement to sell

(b) a sale

(c) both ‘a’ and ‘b’

(d) either ‘a’ or ‘b’

5. A valid sale must have two parties who

(a) must be competent to contract

(b) may not be competent to contract

(c) must be Indian citizens

(d) must be residents of the same state

6. An agreement to sell is

(a) an executory contract

(b) an executed contract

(c) neither ‘a’ or ‘b’

(d) sometime ‘a’ or ‘b’

7. Specific goods are such goods which are

(a) existing and identified at the time of making the contract

(b) identified after the making of contract but before the performance of contract

(c) both ‘a’ and ‘b’

(d) neither ‘a’ nor ‘b’

8. ‘Future goods’

(a) can be the subject matter of sale

(b) cannot be subject matter of sale

(c) sometimes may be the subject matter of sale

(d) depends on circumstances

9. When there is a contract for un-ascertained goods, and goods perish without the fault of the seller or buyer before the risk passes to the buyer, the contract

(a) can be avoided

(b) cannot be avoided

(c) becomes void

(d) becomes unenforceable

10. To constitute a Contract of Sale, the transfer of property in goods

(a) must be for monetary consideration

(b) may be for non-monetary consideration

(c) must be for both monetary and non-monetary consideration

(d) may be either monetary or non-monetary consideration

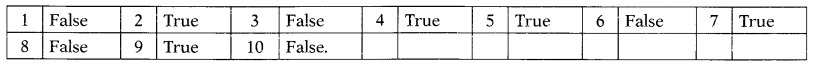

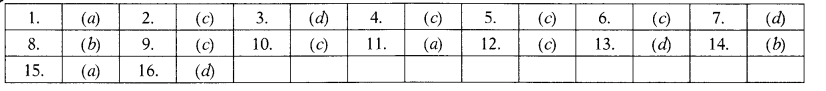

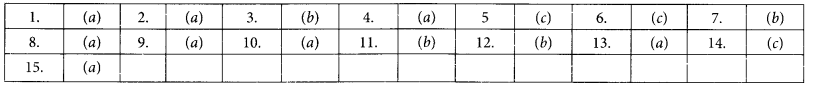

Answers:

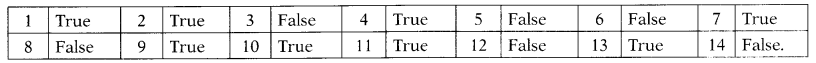

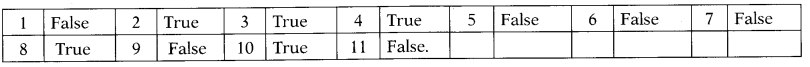

STATE WHETHER THE FOLLOWING ARE TRUE OR FALSE:

1. The term “goods” under Sale of Goods Act, 1930 includes actionable Claims.

2. The Sale of Goods Act, 1930 deals with movable goods only.

3. The Sale of Goods Act, 1930 covers mortgage and pledge of goods.

4. The provisions of Sale of Goods were originally contained in the Indian Contract Act, 1872.

5. In case of hire purchase the hirer can pass title to a bona fide purchaser.

6. In a contract of sale, subject matter of the contract must always be money.

7. In a contract of sale. The agreement may be expressed or implied from the conduct of the parties.

8. The property in goods means possession of goods.

9. The goods are at the risk of the party who has the ownership of the goods.

10. A lady gave a plain saree to Jariwala Brothers for embroidering with lari, to be purchased by Jariwala Brothers. It was held by the court that it was contract of sale.

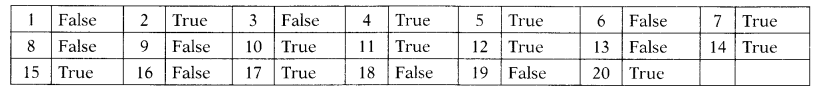

Answers: