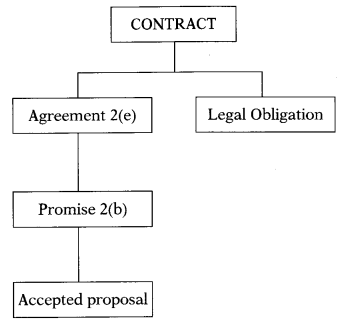

CA Foundation Business Laws Study Material Chapter 5 Free Consent

WHAT IS CONSENT?

Section 13: “Two or more persons are said to consent when they agree upon the same thing in the same sense ”.

Consent involves a union of the wills and an accord in the minds of the parties. When the parties agree upon the same thing in the same sense, they have consensus ad idem. If there is no consent, there is no contract. Salmond states it as error in consensus.

WHAT IS FREE CONSENT?

Section 14 lays down that consent is not free if it is caused by

- coercion,

- undue influence,

- fraud,

- misrepresentation, or

- mistake.

If the consent is not free then it is known as error in cause.

The effect of absence of free consent on contract depends on various factors as mentioned in this chapter. Let us see them all one by one.

WHAT IS COERCION?

Coercion is defined by section 15 of the Act as follows: Coercion is the:

- committing or threatening to commit, any act forbidden by the Indian Penal Code or

- unlawful detaining, or threatening to detain, any property

- to the prejudice of any person whatever

- with the intention of causing any person to enter into an agreement.

Explanation – It is immaterial whether the Indian Penal code is or is not in force in the place where the coercion is employed.

Whether threat to commit suicide amounts to coercion?

The Madras High Court in Amiraju v Seshamma (1918) held by majority that threat to commit suicide amounts to coercion. The Court observed that though suicide was not punishable by IPC, yet it was one forbidden by the IPC, since an attempt to commit suicide is punishable. In this’ case a person threatened to commit suicide if his wife and son did not contract with his brother to release certain disputed property in his favour. The court held that the contract was caused by coercion.

Consequences of coercion

A contract brought about by coercion is voidable at the option of the party whose consent was so caused. [Sec. 19],

WHAT IS UNDUE INFLUENCE?

A contract is said to be induced by undue influence where:

- one of the parties is in a position to dominate the will of the other and

- he uses the position to obtain an unfair advantage over the other Sec. 16(1).

Section 16(2) provides that a person is deemed to be in a position to dominate the will of another where:

- Where he holds a real or apparent authority over the other (For ex- master & servant, ITO & Assessee)

- Where he stands in a fiduciary relationship to the other. Fiduciary relationship means a relationship of mutual trust and confidence. Such a relationship is supposed to exist in the following cases – father and son; guardian and ward; solicitor and client; doctor and patient; preceptor and disciple; trustee and beneficiary etc.

- Where a party makes a contract with a person whose mental capacity is temporarily or permanently affected by reason of age, illness, or mental or bodily distress.

- Where the contract is apparently unconscionable (i.e.; unfair). Ex.: an unfair money lending transaction.

The following relationships usually raise a presumption of undue influence, viz:

- Parent and child,

- guardian and ward,

- trustee and beneficiary,

- doctor and patient,

- lawyer and client,

- spiritual guru and disciple. This list, however, is not exhaustive.

There is no presumption of existence of a power to dominate the will of another in the following cases:

(a) Landlord and tenant,

(b) Creditor and debtor,

(c) Husband and wife.

It has been held by judicial decisions that in all these cases, the party alleging undue influence must prove that undue influence existed.

Example I. A, a man enfeebled by disease of age, is induced by B’s influence over him as his medi-cal attendant, to agree to pay B an unreasonable sum for his professional services. B has employed undue influence.

Example II. A, being in debt to B, the money-lender of his village, contracts a fresh loan on terms which appear to be unconscionable. It lies on B prove that the contract was not induced by undue influence.

Example III. A applies to a banker for a loan at a time when there is stringency in the money mar-ket. The banker declines to make the loan except at an unusually high rate of interest. A accepts the loan on these terms. This is a transaction in the ordinary course of business, and the contract is not induced by undue influence.

Burden of Proof. Section 16(3)

“Where a person who is in a position to dominate the will of another, enters into a contract with him, and the transaction appears, on the face of it or on the evidence adduced, to be unconscio-nable, (unfair, unreasonable) the burden of proving that such contract was not induced by undue influence shall be upon the person in a position to dominate the will of the other.” Thus, in case of unconscionable transactions, the dominant party is under the burden to prove that undue influence was not employed. (In other cases, the burden of proof is on the weaker party to prove that undue influence was employed.)

The presumption of undue influence can be rebutted by the dominant/stronger party by showing that:

- All material facts were disclosed to the party who is alleging exercise of undue influence.

- The consideration was adequate.

- The party alleging exercise of the undue influence was in receipt of independent advice and was free to exercise it.

- The transaction was fair.

Pardanashin women: A pardanashin woman is one who, by virtue of the custom of her community, is required to live behind a veil and is totally secluded from ordinary social interaction. Any contract made by such a women is under the presumption of undue influence.

Effect of Undue Influence

(a) According to Section 19 of the Contract Act, when a contract is induced by undue influence, it is voidable at the option of the aggrieved party, i.e., the party whose consent is obtained by undue influence.

(b) According to Section 19A, any such contract may be set aside by the Court absolutely. However, if the aggrieved party has received any benefit thereunder, it may be set aside upon such terms and conditions as are just in the eyes of the Court.

Example: A, a money-lender, advances Rs. 10,000 to B, a farmer and by undue influence, induces B to execute a bond for Rs. 20,000 with interest at 48 percent per year. The court may set the bond aside, ordering B to repay Rs. 10,000 with such interest as may seen just.

Difference between Coercion and Undue Influence

Points | Coercion | Undue influence |

Type of force | Coercion involves use of physical force. | Undue influence involves use of mental pressure. |

Relationship | In case of coercion, there is no relationship between the parties to the contract. | Whereas in case of undue influence some sort of relationship generally exists between the two parties. |

Third Party | Coercion may be employed either against the party to the contract or against any third person who is not a party to the contract. | Undue influence is exercised against a person who is a party to the contract. No third party is involved in creating undue influence. |

Presumption | The Court cannot draw the presumption of coercion. | The Court may draw the presumption of undue influence if the circumstances so warrant it. |

Effect | The contract is voidable at the option of one of the parties of the contract. | The contract is either voidable or the Court may enforce it in a modified form. |

WHAT IS MISREPRESENTATION?

Representation is a statement or assertion, made by one party to the other, before or at the time of the contract, regarding some fact relating to the contract. Misrepresentation arises when the representation made is untrue but the person making it believes it to be true. There is no intention to deceive. Misrepresentation is misstatement of facts by one, which misleads the other.

Section 18 of the Contract Act classifies cases of misrepresentation into three groups as follows:

(a) Unwarranted Assertion

When a person makes a positive statement of material facts honestly believing it to be true though it is false, such act amounts to misrepresentation.

Example: X while selling his car to Y, informs him that the car runs 18 kilometres per litre of petrol. X himself also believes this. Later on, Y finds that the car runs only 12 kilometres per litre. This is a case of misrepresentation by X.

(b) Breach of duty

“Any breach of duty, without an intent to deceive, which brings an advantage to the person committing it, by misleading another to his prejudice amounts to misrepresentation”. Under this heading would fall cases where a party is under a duty to disclose certain facts and does not do so and thereby misleads the other party. Such a duty exist between the insurer and the insured; banker and customer; landlord and tenant; seller and buyer; and all contracts of utmost good faith. In English law such cases are known as cases of “constructive fraud.”

Example: X while selling his land to Y, told him that all the farms on the land were fully let out. But he negligently omitted to inform him that the tenants had given notice to quit. Here, X is liable for misrepresentation.

(c) Innocent Mistake

If one of the party causes the other, however, innocently, to make a mistake as to the nature or substance of the agreement, it is considered misrepresentation.

Example: In a case, X chartered a ship to Y, which was described in the charter-party (lease or hire contract), and was represented to him as being not more than 2,800 tonnage registered. It turned out that the registered tonnage was 3,045 tons. Y refused to accept the ship in fulfil¬ment of the charter-party (i.e., an agreement between a ship owner and merchant for the use of a ship). It was held that Y was entitled to avoid the charter-party by reason of erroneous statements as to tonnage (The Ocean Steam Navigation Co. v. Soonderdas Dhurumsey, 1890, 14 Bom. 241).

Consequences of Misrepresentation

In case of misrepresentation the aggrieved party can:

- avoid the agreement, or

- insist that the contract be performed and that he shall be put in the position in which he would have been if the representation made had been true. But if the party whose consent was caused by misrepresentation had the means of discovering the truth with ordinary dili-gence, he has no remedy. [Sec. 19]

“Ordinary diligence” means such diligence as a reasonably prudent man would consider necessary, having regard to the nature of the transaction.

Example: A informs B that his estate is free from encumbrance. B thereupon buys the estate. In | fact, the estate is subject to mortgage, though unknown to A also. B may either avoid the contract | or may insist on its being carried out and the mortgage debt redeemed.

WHAT IS FRAUD?

The term “Fraud” includes all acts committed by a person with a view to deceive another person. | “To deceive” means to “induce a man to believe that a thing is true which is false”. Fraud is a false | statement or wilful concealment of a material fact with an intent to deceive another party.

Section 17 of the Contract Act states that “Fraud” means and includes any of the following acts:

(i) False Statement

“The suggestion as to a fact, of that which is not true by one who does not believe it to be true”. A false statement intentionally made is fraud.

Example: X while selling his car to Y says that it is of the latest model and brand-new knowing fully well that it is a used car of old model. His representation or statement amounts to fraud.

(ii) Active Concealment

“The active concealment of a fact by one having knowledge or belief of the fact.” Mere non-disclosure is not fraud where the party is not under any duty to disclose all facts. But ! active concealment is fraud.

Example: X, a scooter dealer, showed a scoQter to Y, X knew that its handle and body are cracked which he had repaired in such a way as to defy detection. The defect was subsequently discovered by Y. Hence he refused to buy the scooter. Here, the contract could be avoided by Y as his consent was obtained by fraud.

(iii) Intentional non-performance

“A promise made without any intention of performing it”.

Example: Purchase of goods without any intention of paying for them.

(iv) Deception

“Any other act fitted to deceive”.

Example: X, with an intention to deceive Y, makes a false statement to him that the sales from his shop are to the tune of Rs. 2,000 per day, although X is aware that they amount to Rs. 1,000 per day only. Y is induced to buy the shop. Here, the statement of X amounts to fraud.

(v) Fraudulent act or omission

“Any such act or omission as the law specially declares to be fraudulent”. This clause refers to provisions in certain Laws, which declare certain acts or omissions to be fraudulent.

Example: Thus, under section 55 of the Transfer of Property Act the seller of immovable property is bound to disclose to the buyer all material defects. Failure to do so amounts to fraud. In the insolvency legislations, the fraudulent preference to creditors is not allowed.

Note: A deceit which does not deceive is no fraud. This means that if the promisee is not deceived or did not rely on the representation then there is no fraud. Fraud must have been made with an intention to deceive and must actually deceive the other party. Also, the party subjected to fraud must have suffered some loss.

Consequences of Fraud.

A party who has been induced to enter into an agreement by fraud has the following remedies open to him. [Sec. 19]

- He can avoid the performance of the contract.

- He can insist that the contract shall be performed and that he shall be put in the position in which he would have been if the representation made had been true.

- The aggrieved party can sue for damages.

Can Silence be Fraudulent?

“Mere silence as to facts likely to affect the willingness of a person to enter into a contract is not fraud, if the circumstances of the case are such that, regard being had to them, it is the duty of the person keeping silence to speak, or unless his silence is, in itself equivalent to speech”. [Explanation to sec. 17]

Example I: H sold to W certain pigs. The pigs were suffering from fever and H knew it. The pigs were sold “with all faults”. H did not disclose the fever to W. Held :There was no fraud [ Ward v. Hobbs (1878) A. C. 13],

Example II: A sells by auction to B, a horse which A knows to unsound. A says nothing to B about the horse’s unsoundness. This is not fraud by A. Mere non-disclosure is not fraud. If there is no duty to speak.

Example III: A and B, being traders enter upon a contract. A has private information of a change in prices which would affect B’s willingness to proceed with the contract. A is not bound to inform B.

From the above, following rules can be deduced:

- The general rule is that mere silence is not fraud.

- Silence is fraudulent, “if the circumstances of the case are such that, regard being had to them, it is the duty of the person keeping silence to speak”. The duty to speak, Le. disclose all facts exists where there is a fiduciary relationship between the parties (such as in father and son; guardian and ward, etc, and also in the insurance contracts, marriage contracts, partnership contract etc which are contracts based on good faith [contracts of uberimae fidei]). The duty to disclose may also be an obligation imposed by statute.

Example: A sells by auction to B, a horse which A knows to be unsound. B is A’s daughter and has just come of age. Here the relation between parties would make it A’s duty to tell B if the horse is unsound. - Silence is fraudulent where the circumstances are such that “Silence is in itself equivalent to speech”.

Example: B says to A – “If you do not deny it, I shall assume that the horse is sound.” A says nothing. Here A’s silence is equivalent to speech.

Difference between Misrepresentation and Fraud

S.No | Points of Difference | Misrepresen ta Hon | Fraud |

1. | Different | In misrepresentation there is no intention to deceive. | Fraud implies an intention to deceive. |

2. | Different | The person believes it to be true. | The person believes and makes false statements. |

3. | Different | In case of misrepresentation the only remedy is rescission. There can be no suit for damages. | In case of fraud the aggrieved party can rescind the contract. He can also sue for damages. |

4. | Different | The aggrieved party cannot avoid the contract if he had the means to discover the truth with ordinary diligence. | But in case of fraud excepting fraud by silence, the contract is voidable even though the party defrauded had the means of discovering the truth with ordinary diligence. |

WHAT IS MISTAKE? WHAT IS THE EFFECT OF MISTAKE ON CONTRACT?

Mistake may be defined as an erroneous belief concerning something. It may be of two kinds:

- Mistake of Law

- Mistake of Fact.

(1) MISTAKE OF LAW

Mistake of law may be of two types—

(a) Mistake of general law of country

Every one is deemed to be conversant with the law of his country, and hence the maxim “ignorance of law is no excuse.” Mistake of law, therefore, is no excuse and it does not give right to the parties to avoid the contract. If a mistake of law leads to a formation of contract, section 21 enacts that a contract is not voidable because it was caused by a mistake as to any law in force in India ’’.

A person cannot get any relief on the ground that he had entered into a contract in ignorance of law.

Illustration: A and B make a contract grounded on the erroneous belief that a particular debts is barred by the Indian law of limitation; the contract is not voidable.

(b) Mistake of Foreign Law:

Mistake of foreign law is treated as ‘mistake of fact’. Here the law relating to factual mistakes will apply.

(2) MISTAKE OF FACT

Mistake of Fact may be of two types:—

(a) Bilateral mistake

In case of bilateral mistake of essential fact, the agreement is void ab-initio. Section 20 pro-vides that “Where both the parties to an agreement are under a mistake as to a matter of fact essential to the agreement is void.’’ Thus for declaring an agreement void ab-initio under this section, the following three conditions must be fulfilled:

- Both the parties must be under a mistake.

- Mistake must relate to some fact and not to judgment or opinion etc. An erroneous opinion as to the value of the thing which forms the subject-matter of the agreement is not to be deemed a mistake as to a matter of fact (Explanation to Section 20).

- The fact must be essential to the agreement i.e., the fact must be such which goes to the very root of the agreement.

On the basis of judicial decisions, the mistakes which may be covered under this condition may broadly be put into the following heads:

- Mistake as to the existence of the subject-matter of the contract.

Ex.: A agrees to buy from B a certain horse. It turns out that the horse was dead at the time of the bargain, though neither party was aware of the fact. The agreement is void. - Mistake as to the title of the subject-matter.

Ex.: A believed that she had inherited rights over a fishery from her father. B, her cousin brother, also believed in A’s rights. B agreed to take the fishery on lease from A. Actually the fishery belonged to B. The agreement, caused by mistake as to title, was held to be void (Cooper v. Phibbs (1867) LR HL 149). - Mistake as to the quantity of the subject-matter.

Ex.: P wrote to H inquiring the price of rifles and suggested that he might buy as many . as 50. On receipt of the information, he telegraphed “Send three rifles.”But because of the mistake of the telegraph authorities, the message transmitted was “Send the rifles. ” H dispatched 50 rifles. Held: There was no contract between the parties. However, P could be held liable to pay for three rifles on the basis of an implied contract [Henkel v. Pape (1870) 6 Ex. 7]. - Mistake as to the quality of the subject-matter.

Ex.: X agreed to sell to Y an antique item believed by X to be of the 18th Century. What Xpossessed was actually of the 20th century. So the bilateral mistake about quality of the subject-matter makes it a void agreement.

(b) Unilateral Mistake

Where only one of the contracting parties is mistaken as to a matter of fact, the mistake is a unilateral mistake. Regarding the effect of unilateral mistake, on the validity of a contract, sec. 22 provides that “A contract is not voidable merely because it was caused by one of the parties to it being under a mistake as to a matter of fact”.

Law regarding unilateral mistake

(1) Contract Valid: As a rule, a unilateral mistake is not allowed as a defence in avoiding a contract Le., it has no effect on the contract and the contract remains valid.

(2) Contract voidable: If the unilateral mistake is caused by fraud or misrepresentation etc., on the party, the contract is voidable and can be avoided by the injured party.

(3) Agreement void ab-initio; In the following two cases, where the consent is given by a party under a mistake which is so fundamental as goes to the root of the agreement and has the effect of nullifying consent, no contract will arise even though there is a unilateral mistake only.

(a) Mistake as to the identity of person contracted with, where such identity is important. If A intends to contract with B only, but enters into contract with C believing him to be B, the contract is void.

Example:

- In Cundy v. Lindsay & Co., (1878) 3 App. Cas. 459., A company (Lindsay & Co.) had regular dealing with a firm Blenkiron & Co., having office in Wood Street. Another person with a similar name, Blenkarn, maintaining an office in the same street, sent an order on its printed letter head to the company for purchase of some goods. The company were led to believe that the order came from the famous firm they knew. They sent the goods. The fraudulent Blenkarn sold the received goods down to Cundy. In a suit by Lindsay against Cundy for recovery of goods, it was held that as Lindsay never intended to contract with Blenkarn, there was no contract between them and as such even as innocent purchaser of the goods from Blenkarn did not get a good title, and must return them or pay their price.

Further, “Mistake as to the identity” of a party is to be distinguished from “mistake as to the attributes” of the other party. Mistake as to attributes, for example, as to the solvency or social status of that person cannot negate the consent. It can only vitiate consent. It therefore, makes the contract merely voidable for fraud.

Thus, where X enters into a contract with Y falsely representing himself to be a rich man, the contract is only voidable at the option of Y. Again where the identity of the party contracted with is immaterial, mistake as to identity will not avoid a contract. Thus, if X enters a shop introduces himself as Y and purchased some goods for cash, the contract is valid.

Example:

- Philips v. Brooks (1919) 2 KB 243 – In this case a man, N, called in person at a jeweller’s shop and chose some jewels, which the jeweller was prepared to sell him as a casual customer. He tendered in payment a cheque which he signed in the name G, a person with credit. Thereupon N was allowed to take away the jewels which N pledged with B who took them in good faith. Held, the pledge, B, had a good title since the contract between N and the jeweller could not be declared void on the ground of mistake but was only voidable on the ground of fraud. Horridge, J. held that although the jeweller believed the person to whom he was handling the jewels was G, he in fact contracted to sell and deliver to the person who came into his shop. The contract, therefore, was not void on the ground of mistake but only voidable on the grounds of fraud.

(b) Mistake as to the nature and character of a written document. The second circumstance in which even an unilateral mistake may make a contract absolutely void is where the consent is given by a party under a mistake as to the nature and character of a written document. The rule of law is that where the mind of the signatory did not accompany the signature; i.e., he did not intend to sign; in contemplation of law, he never did sign the contract to which his name is appended and the agreement is void ab-initio.

Example: In case of Foster v. MacKinnon (1868) LR 4 CP 704, an old illiterate man was made to sign a bill of exchange, by means of a false representation that it was a guarantee. Held: the contract was void.

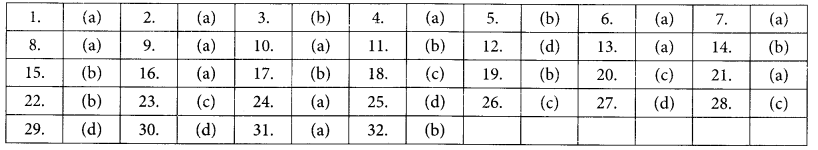

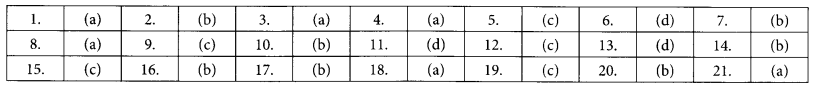

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS:

1. If there is no consent the agreement is:

(a) Void

(b) Voidable

(c) Illegal

(d) Valid

2. If consent in not free due to coercion, undue influence, fraud, and misrepresentation then the agreement is:

(a) Void

(b) Voidable

(c) Illegal

(d) Valid

3. If the agreement is made by obtaining consent by doing an act forbidden by the Indian Penal Code, the agreement would be caused by:

(a) Coercion

(b) Fraud

(c) Misrepresentation

(d) Undue influence

4. A buys an article thinking that it is worth Rs. 100 when in fact it is worth only Rs. 50. There has been no misrepresentation on the part of the seller. The contract is:

(a) Valid

(b) Void

(c) Voidable

(d) Unenforceable

5. Where a person is in a position to dominate the will of another person and uses that position to obtain on unfair advantage it is called:

(a) Fraud

(b) Coercion

(c) Undue influence

(d) Misrepresentation.

6. An agreement caused by unilateral mistake of fact is:

(a) Void

(b) Voidable

(c) Illegal

(d) Valid

7. Unlawfully detaining or threatening to detain any property, to the prejudice of any person making him to enter into an agreement amounts to:

(a) Threat

(b) Coercion

(c) Undue influence

(d) Misappropriation

8. An agreement made under mistake of fact, by both the parties, forming the essential subject matter of the agreement is:

(a) Void

(b) Voidable

(c) Valid

(d) Unenforceable

9. “Active concealment of fact” is associated with which one of the following?

(a) Misrepresentation

(b) Undue influence

(c) Fraud

(d) Mistake

10. Lending money to a borrower, at high rate of interest, when the money market is tight renders the agreement of loan:

(a) Void

(b) Valid

(c) Voidable

(d) Illegal

11. When a person, who is in dominating position, obtains the consent of the other by exercising his influence on the other, the consent is said to be obtained by:

(a) Fraud

(b) Intimidation

(c) Coercion

(d) Undue influence

12. With regard to the contractual capacity of a per-son of unsound mind, which one of the following statements is most appropriate?

(a) A person of unsound mind can never enter into a contract

(b) A person of unsound mind can enter into a contract

(c) A person who is usually of unsound mind can contract when he is, at the time of entering into a contract, of sound mind

(d) A person who is occasionally of unsound mind can contract although at the time of making the contract, he is of unsound mind

13. While obtaining the consent of the promisee, keeping silence by the promisor when he has a duty to speak about the material facts, amounts to consent obtained by:

(a) Coercion

(b) Misrepresentation

(c) Mistake

(d) Fraud

14. ‘A’ threatened to commit suicide if his wife did not execute a sale deed in favour of this brother. The wife executed the sale deed. This transaction is:

(a) Voidable due to under influence

(b) Voidable due to coercion

(c) Void being immoral

(d) Void being forbidden by law

15. A threatens to shoot B, if B does not agree to sell his property to A at a stated price. B’s consent in this case has been obtained by

(a) Fraud

(b) Undue influence

(c) Coercion

(d) None

16. A master asks his servant to sell his cycle to him at less than the market price. This contract can be avoided by the servant on grounds of:

(a) Coercion

(b) Undue influence

(c) Fraud

(d) Mistake

17. If A sells, by auction to B a horse which A knows to be unsound and A says nothing to B about the horse’s unsoundness, this amounts to:

(a) Fraud

(b) Not fraud

(c) Unlawful

(d) Illegal

18. Silence is fraud when silence is, in itself equivalent to speech. This statement is:

(a) True

(b) False

(c) Untrue in certain cases

(d) None of these

19. A person is deemed to be in a position to dominate the will of another if he:

(a) Holds real or apparent authority

(b) Stands in a fiduciary relationship

(c) Both (a) and (b)

(d) Either (a) or (b)

20. If both the parties to a contract believe in the existence of a subject, which infact does not exist, the agreement would be

(a) Unenforceable

(b) Void

(c) Voidable

(d) None of these

21. When both the parties to an agreement are under a mistake as to a matter of fact essential to an agreement, the agreement is:

(a) Void

(b) Valid

(c) Voidable

(d) Illegal

Answers:

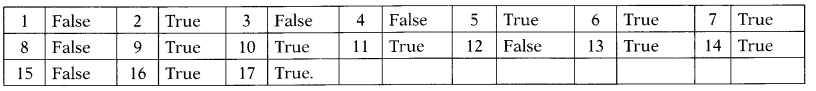

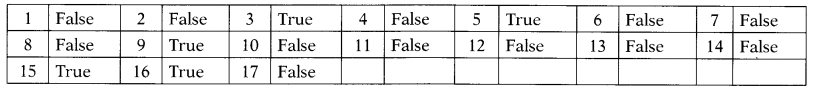

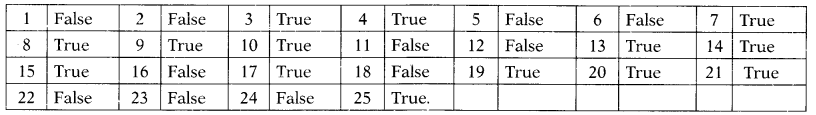

STATE WHETHER THE FOLLOWING ARE TRUE OR FALSE:

1. A threat to commit suicide does not amount to coercion.

2. A deceit which does not deceive is no fraud.

3. Consent obtained by fraud makes the agreement void.

4. A person who is usually of unsound mind but occasionally of sound mind can always enter into contract.

5. Mere silence as to facts likely to affect the willingness of a person to enter into contract is not fraud.

6. A contract is not voidable merely because it was caused by one of the parties to it being under a mistake as to a matter of fact.

7. In the absence of consent, there can be no contract.

8. A threat amounting to coercion must necessarily proceed from a party to the contract.

9. Undue influence involves use of moral pressure.

10. Undue influence can be exercised only by a party to the contract.

11. If there is no damage, there is no fraud.

12. In case of fraud, the aggrieved party loses the right to rescind the contract if he had the means of dis-covering the truth by ordinary diligence.

13. Undue influence can be exercised only between the parties who are related to each other.

14. A promise made without any intention of performing it amounts to fraud.

15. If one of the parties to a contract was under a mistake as to the matter of fact, the contract is voidable.

16. Ignorance of foreign law is put on a same level with ignorance of fact.

17. A contract is not voidable only because there is a mistake of Indian law.

Answers: